The Arab Culture Capital 2004Sana’a: Glory of the past and future [Archives:2003/698/Culture]

December 29 2003

|

|

|

[email protected]

For the Yemen Times

Sana'a, the capital of the Republic of Yemen, is an oasis amidst the rugged Sarat Mountains along the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula. For centuries the isolated home of Yemeni imams, this ancient city has been reborn. It reinvented itself to respond to developments of modern Republic of Yemen. It has grown into modern metropolis, and is on its way to become an “Southern Arabian Business Meeting Point”.

On its busy avenues and quiet shaded lanes Sana'a buys and sells, boils and plays, celebrates life and mourns its passing. As syntheses of dreams it is a bustling oasis in the flow of life events. Sana'a lies sprawled at the foot of Jebel Nugum which may have been a dominant influence on the original choice of the site of the settlement. The capital's perimeter is continually expanding outward. Sana'a is developing expanding city which retains its unique and intriguing blend of old and new.

Nestled on a fertile plateau at an altitude of 2.400 m the city has a perfect climate – long summers of warm, sunny days and cool, clear evenings, and mild winters with brisk nights. Over many generations the farmers of Sana'a have carefully terraced the surface of the plain for cultivation wherever terrain and soils permit. All around Sana'a as far as the eye could see, were ranges of hills ornamented with countless houses in brick and stone. The humidity is very low and, at certain times of the year, a layer of dust hazes the horizon and the wind send twisting swirls of dust across the plain.

Plain is brown, the mountains blue and foothills are tawny and purple. Plain and hills are capable of a hundred shades that with and changing light slip over the face of the land. The light here is a living being, always austere, always grand, never sentimental. The light and the space, and the color that sweep in ways of brown color of the earth, reflecting the color of age. Despite little rainfalls, the fields surrounding Sana'a are green with apricot trees, almond and walnut groves.

It is spring and the near bye valleys are full of Apricot blossoms.

The rains were carrying now cloudy night skies, and other gifts the wind had given it. Like fine rain from a thick cloud. In a while the rains slowed to a drizzle and then stopped. The breeze shock water from the trees in the near bye Wadi Dahr valley, and at Hadda village for a while it rained only under trees.

The oldest living city in Yemen, Sana'a has existed since at least 540 AD. In the years before Islam, it was already the home of kings, who dwelt in the towering Ghamdan Palace. Caravans of spices, incense and balsam journeyed northward from its samsarahs, returning to fill the bustling markets with silk, indigo, brass and silver.

An account from eighteenth century describes

“pillared temples and sumptuous palaces where court from silk dais and domed pavilions, and where gushing fountains watered fruit and flower gardens of every variety”.

Luring travelers across the forbidding mountains and unrelenting deserts of Yemen, the remote, mystical city of Sanaa, was eulogized the “Pearl of Arabia”.

Yet in sharp contrast to modernization, the city of Sanaa retains an un-spoiled charm, created by a unique architectural design and a way of life. Its inhabitants dwell in atmosphere of mosques, minarets, palaces, ancient walls and bazaars side by side with most recent technological achievements.

Changes in Sana'ani patterns of living have occurred in the last two decades, resulting from expatriates coming into the city and from exposure of men and women, both through travel and television and education, to life in other countries. The older generation admits that customs and mores, especially those involving the role for women, are now changing so rapidly that the lives of their sons and daughters will scarcely resemble their own.

For many centuries, the city of Sana'a was within a walled area which now lies in the eastern sector of the modern capital. Today the city has by far outgrown these walls but, the pulse of social and commercial activity still throbs vibrantly in the Old Town. The tide of inhabitants is swelled by a constant flow of tribesmen from outlying villages, shoppers from the western sector of the city, and tourist both local and foreign. They come to shop, exchange news and information, or simply to experience the beat of Sana'ani life.

It is here, in the labyrinth of markets, houses, samsarahs and mosques, threaded by a network of narrow lanes and open squares, that the contrasts of different eras are most dramatic. The ancient city succumbs to the impudent, haphazard intrusion, and western goods, and the visitor is baffled and amused by and hotchpotch of new and old and “the latest”.

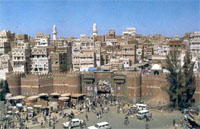

The approach to the Old Town along Zubairi Street, is one of the most attractive sights in Sana'a. The mud brick walls, built to keep tribal marauder from a medieval trading town, now stretches around a dense, bustling metropolitan quarter. Above it rises an enchanting medley of brown, multi-stored-stored stored building, the plaster tracery on their facades giving them an appearance of fantasy “gingerbread” houses. Crowded together over centuries of reconstruction and expansion, their walls and rooftops rise in amiable irregularity to form meandering staircases in the sky. The white-trimmed, mud brick houses characterize Sana'ani architecture. Sanaa is a place of houses and people not of spaces. Yemen is famous for its architecture, and the houses of Sanaa are imposing monuments to the cities unique expression of traditional Yemeni design, and life style which endured over centuries.

Along the western side of the Old Town is the sailah, the riverbed for seasonal rainfall that flows from the mountains southeast of the city. The sailah has been turned into thoroughfare road, but several times in the past its banks have overflowed, flooding the Old Town.

At the end of Zubairi Street is Bab Al-Yemen, the only remaining gate of the original five into the Old Town. A two way- stream of pedestrians, automobiles, motorbikes and donkey carts pour through the wide stone arch, and its two large wooden doors, closed and barred at sunset each evening during the reign of the imams, are now open days and night.

The smell of it, the feel of it:

The Old Town is as much abuzz now as it was a quarter century ago. It smells of spices and orange blossoms, roasting coffee, lamb kebabs, and fragrances of balm and herb spices which are an integral part of Yemeni cuisine, takes on every form, color and tastes. Never before I set foot in a city, never observed the swarming activity of the alley ways, never felt that powerful breath on my face, like the wind from the sea heavy with cries and smells.

But the Old City rises early each morning with more bustle, more color, more voice. The suq, or market, begins just inside Bab Al-Yemen, where traveling salesman auctions coats and jackets and boys push wheelbarrows piled high with striped futahs and brass incense burners. Fruit and vegetables are also sold here. Breads, onions, potatoes, tomatoes and water melons. Jasmin and incense. Raisins with the color of henna. Papayas and mangos from the Tihama. Melons from Sadah, Oranges from Marib. Rose water in bottles. Grapes and dates. Almonds and nuts. Along with candy, jewelry, scissors and flash lights, woven baskets.

The streets soon fork and narrow into Suq-al-Milh, where shops selling similar items are clustered together in quarters. The local residents admire colorful displays of Persian carpets, mafraj mattresses, fabrics from the Tihama with pattern of the sun, Metal suitcase from India. Spice and grain merchants dip wheat, sorghum and lentils form woolen sacks, coffee beans and husks from leather bags, and garlic bulbs, chilies, and peppercorn from basket trays.

From its green geometric terraces and valleys

Customers buy quantities of cumin, ginger, cardamom, or plastic bags of raisins, fresh dates and almonds. Rock salt from the coastal area of Salif or the mines near Marib is sold in two-kilo sacks made of plaited palm leaves. From their booths lined with old apothecary cabinets vendors casually produce amber – colored myrrh and brown frankincense, the famous resins of Arabia Felix, crystals of white musk and tinny vials of thick, brown ambergris, which lend their distinctive odors to countless perfumes.

Interspersed among the single-level stalls and workshops of the market areas are several multi-stored samsarahs, or caravansaries. Most of these samsarahs are very old, one dates from the fourteenth century, and are remnants of the days when caravans of myrrh, frankincense, and spices passed through Sanaa on their way to the Mediterranean. Passing through the swarming alleys, followed by imposing caravans, loaded with all sorts of merchandise. In Sanaa the good were weighed and inspected and the tax paid. Merchandise destined for the City was also lodged in the samsarahs.

It was here that Heavens poured countless riches. The wayfarers would for weeks and months proceeding in the same direction to Sana'a. Then all lands seemed far away even the land one comes from or the land one is crossing.

Today caravans come no more.

Samsarahs have been turned into art and craft centers. But smells like music hold memories. To think thoughts and not voice them. Long after the houses and palaces and ourselves have disappeared. A faint smell of incense floated all around.

Away from the market of shops and samsarahs, overlooking wider lanes and open squares, are brown mud-brick tower houses of the Old Town. Scattered among the streets and houses, an integral part of life in the Old Town are over forty mosques, the place of prayer, meeting, and mediation. Many of the mosques in the Old Town are simple, walled structures with an open courtyard. Around these are large prayer galleries with flat roofs. The most impressive mosque in the Old Town is al-Jami al-Kbir, the Grand mosque. Its wooden ceilings are carved with floral patterns and inscribed with Koranic verses. Here the perfume vendors in front of the Grand Mosque dispenses a hundred scents some as ancient as the trade routes from the East, others as modern as yesterday Paris fashion.

The night now hid his face and murmur of a number of prayers. Always below street level, are small green oases in a city devoid of any free- growing shrubs and flowers. In the Old Town are at least fifteen Turkish bath houses, their low roofs topped by numerous small domes.

There is a lasting fascinations for all those who come to know Sana'a, a city fast integrating into twenty first century concepts, and customs with a rich and ancient heritage.

——

[archive-e:698-v:13-y:2003-d:2003-12-29-p:culture]