The Yemeni Parliamentary Elections: A critical analysis [Archives:2006/976/Reportage]

August 28 2006

|

This article examines the political, legal, and socio-economic framework of previous parliamentary elections. Among the real problems that threaten the Parliament are poverty and mismanagement of resources. The state becomes the main source of wealth and power; therefore, competition for authority has to be zero-sum, decreasing the possibility of resolving political disputes through systematic institutional processes. By the same token, culture is one of the main factors that have affected the Parliament through affecting party systems and electoral behaviour.

Political Sphere

The short span since the establishment of the Yemeni Parliament in 1990 does not permit extensive institutionalisation and consolidation; nonetheless, Yemen has had three consecutive parliamentary elections in 1993, 1997 and 2003. During the respective elected councils the Parliament has functioned in an unstable political environment. Political life has been characterised by a struggle for power, swinging from co-operation to a large-scale war. Depending on the level of tension between different parties, power distribution, and the impact on the Parliament, Yemeni parliament swings from semi efficient and relatively autonomous to an ineffective.

During the first parliament that followed the unification in 1990 the balance of power between rivals provided the Parliament with reasonable room to manoeuvre, and the two ruling parties the General Peoples' Congress (GPC) and the Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP) tried to reach a compromise over many issues. In the process, they delegated considerable authority to the Parliament and 58.4 per cent of the MPs believe that it had high autonomy and 20.8 per cent say it had reasonable degree of autonomy. The Parliament, therefore, emerged as a powerful institution to the extent that it was prepared to withdraw confidence from the government in 1991 for raising diesel prices, whereupon the government retreated.

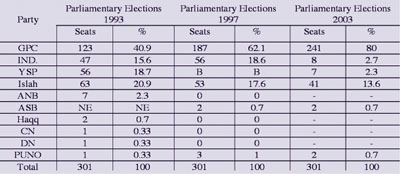

The elections of 27 April 1993 changed the power-sharing formula between the GPC and the YSP. Consequently, the YSP fell back to the third position, behind the GPC and its ally the Islah party, in the number of occupied seats in the Parliament. To maintain the united Yemen framework, the three parties agreed to form a coalition government. Because of the military power the YSP had, it was given more ministerial and administrative posts than was the Islah, the second party.

Nevertheless, the YSP was dissatisfied by the election results and became more vulnerable. Given these results and assassination attempts against its activists, the YSP assumed this was the beginning of a process to abandon it by gradually stripping it of power. The YSP therefore advocated constitutional reforms and new perception for state building as a strategy to bring its rivals down to its level.

A deep conflict emerged which, because of the gap between differing perceptions of the course of future development for Yemen and the declining balance of power between the ruling parties, resulted in the failure to create a joint platform for co-operation. The YSP's only solid support for its position was its control over the army in the south. As time went by, a bitter struggle erupted for governmental, economic, and military power.

This rivalry had its impact on the Parliament. Although the Parliament was more representative than the previous one, it appeared less powerful (48.3 per cent of the MPs believe that it had high autonomy and 40.3 per cent report it had reasonable degree of autonomy), having been affected by the disputing parties who were controlling state administration. The Parliament failed to resolve the political disputes and the war seemed inevitable, which eventually broke out on 5 May 1994. By 7 July 1994 the GPC and its allies had swept through the south and destroyed the military and security capabilities of the YSP.

As the situation deteriorated, the Parliament found itself crippled by the lack of power. However, it is worth noting that the Parliament remained the only functioning unitary institution (including the YSP MPs) during the civil war at a time when all other state institutions had splintered between the two parties. The Parliament lost its relative autonomy during and shortly after the war. Most YSP MPs continued their duties, but they were subjected to a state of fear and lost their organisational coherence. They dealt with different issues individually and incongruently. The GPC and the Islah parties found it easy, therefore, to pass their desired constitutional amendments. On 28 September 1994, the Parliament approved these amendments (1994 Constitution). On 1 October 1994, according to the amendments, the Parliament abolished the Presidential Council in favour of a one-man presidency and Ali Abdullah Salih was re-elected by the MPs as the president of the republic for a five-year term.

After fending off the YSP threat, both the GPC and the Islah started rethinking the formula of power distribution. They approached each other cautiously. Overtly, they claimed to be close allies, but in reality they were competing to build up their power. Fortunately, this allowed the Parliament to resume some of its power.

Another phase started with the 1997 parliamentary election, which resulted in a sweeping victory for the GPC. Despite the majority Parliament, it showed some degree of autonomy stemming from decreasing the threat imposed on the GPC, the fluid nature of the GPC organisation, lack of internal discipline, and the feeling of the MPs that they owed nothing to their party to be in the Parliament. Among the MPs, 47 per cent believe that the Parliament has low autonomy, while only 22.8 per cent believe it has reasonable degree of autonomy. This led the Parliament to generate unpredicted decisions as long as the core interests of the ruling establishment remain untouched.

The current phase has started with the latest parliamentary elections on 27th of April 2003, which again resulted in landslide victory for the GPC 241 seats of the 301 seats and Islah came in the second with 41 seats and YSP with 7 seat and independents and other small parties (Ba'ath and Nasserite) divided the remaining seats.

Electoral and Party Systems

Electoral System

General Election Law No. 27/1996 has adopted the first-past-the-post (FPP) system with single-member constituencies. All election affairs are organised technically by the Supreme Election Committee (SEC), a body charged with the task of preparing for and conducting all elections. This system formula states that the candidate who obtains the most votes wins and all votes for the other candidates are effectively wasted. The 1993, 1997 and 2003 parliamentary elections showed that the FPP system favours the largest parties.

Supporters of this electoral system contend it suits Yemen's circumstances. With the high rate of illiteracy, voters can recognise and choose their candidates on a personal basis. This also provides transparent, easy, and straightforward elections. Moreover, this gives room for independents to be represented in the Parliament. Findings suggest that 69.8 per cent of the MPs support the existing electoral system, which brought them in.

Opponents contend that such a system in a traditional society like Yemen's would increase the importance of kinship preferences, which would deepen the sub-national identity at the expense of party electoral programmes. This downgrading the level of Parliament's professionalism. This system also disfavours small parties, depriving them of representation in Parliament. Opponents instead call for proportional representation (PR), claiming that it minimises personal and financial influences, allows political parties to form coalitions, gives priority to programmes, and enables parties to choose the most qualified, not the most socially influential, candidates.

With regard to representation, however, the existing FPP system shows shortcomings. For example, in the 1997 election, at the constituency level, 116 MPs won with less than half (some as few as 23 per cent) of all votes in their constituencies. At the national level in 2003 elections when adding up all the constituencies' results to get an overall state of the Parliament, all MPs got 55 per cent of all votes cast and 33.5 per cent of all registered eligible voters. The FPP system produces a majority government. In the three elections held in Yemen small parties won 12, 5 and 4 seats in the 1993, 1997 and 2003 elections, respectively. However, in a nascent democracy such as Yemen's, this system probably provides a stable majoritarian government that allows for a certain co-operation between the Parliament and the government. In the short run this is possibly desirable to allow democratic institutions to consolidate and institutionalise further.

Party System

After the unification in 1990 Yemen had over forty political parties, later decreasing to fifteen in order to meet the requirements of Law No. 66/1991 governing organisation and political parties. Among the fifteen parties, nine pre-date the existence of the Parliament.

The prominent feature is the fluid state of most of these parties. The parties are weakened by the traditional context, fragmented social structure, paternalism, and personification of politics that affects parties' organisation and cohesion. In the historical evolution of the parties, severe repression pushed them underground, which has also contributed to weakening inter-party democracy and to the absence of a rational mechanism for decision-making.

Yet most large parties in Yemen did not originate in legislative bodies. They had their roots in local organisations or in the nationalist movement. So these parties, mainly the GPC and the YSP, emerged as single dominant ones benefiting from their links with the founding of the state. Thus, they have retained a known electorate cemented by using state patronage to reinforce their strength. During the interim period (1990-93) both the GPC and the YSP used their control of the state to reward their supporters with jobs and money. After the 1994 war, the GPC continued benefiting from this advantage.

Historical evidence shows a negative relationship between democratic consolidation and electoral volatility. In West European elections between 1885 and 1985 average volatility was 8.6 per cent. The lower it is, the more likely that the electoral arena is well established. The high volatility of the Yemeni party system demonstrates a fractionalised party system. The volatility value increased slightly under the effect of the YSP's boycotting the 1997 election; nonetheless it remains high as shown in 2003.

With regard to party organisation, this explains the relationship between the parliamentary party and the party organisation. So far, only eight parties have been represented in the last two parliaments. Five parties are leftist (the three Nasserite parties, the Ba'ath, and the YSP), two are Islamist (al-Haqq and the Islah), and from the right is the GPC. Apart from the three biggest parties (GPC, YSP, and Islah), other parties have been, in all, represented by only seventeen MPs in the last two Parliaments. The MPs of the small parties are very disciplined and show strong commitment to their parties' policies. Their small number means that their parties and the media put extra pressure on them to be genuine representatives for their parties. Thus, those MPs' behaviour does not reflect systematically the organisation of their parties.

On the other hand, the three big parties show different trends. The MPs representing these parties viewed intra-party discipline as follows: 53 per cent of the GPC call for much higher levels of discipline; 56 per cent of the YSP call for much less; and 60 per cent of the Islah express their satisfaction with the present level of discipline. In all parties, the majority of MPs said there are no sanctions available to their parties against them in case of deviation from party policy, and at most they receive blame.

Parliamentary Campaigns and Elections

The Supreme Election Committee (SEC) decided on the exact boundaries of constituencies, based on the population census estimate of December 1992, which puts the population at 14'256'724. Considering administrative and tribal borders, the SEC come up with 301 constituencies, each to accommodate an average of 47,365 inhabitants, allowing for a variation of plus or minus 5 per cent. To ease polling, geographic proximity, population density, and availability of centrally located public buildings are again taken into consideration to choose election centres. Finally 2017 election centres were identified for all 301 constituencies.

The SEC organised this task through 4'052 committees distributed throughout the country, and these rosters are to be updated every two years. The elections had been handled under supervision of the SEC by 7'262 (in 1993), 13'850 (in 1997) and 25'528 (in 2003) field polling committees.

The statistics from the voting rosters in show that of those who are eligible to vote has increased from only 43 to 70 per cent. Nonetheless, within the 18 governorates the percentage varied from 30 per cent in al-Mahrah to 60 per cent in Aden. There was also extreme refrainment among women; who also show variation: in some conservative provinces, such as al-Jawf, as few as 1 per cent while in more progressive urban areas like Aden the figure was 41 per cent. High rates of illiteracy, the culture, religion, the new practices of democracy in Yemen, and people's distrust of the regime's democratic orientation all diminished the registered numbers.

The Opposition parties had been complaining that there were serious problems in the voter registration process, which disadvantaged localities with strong support for the opposition. Issues raised included allegations of using multiple registrations; registration of underage persons; and moving military forces in order to register them in certain constituencies to shift election results. These allegations were repeated over the three elections as well as in the presidential election in 1999.

The high number of independent candidates reflects the fragmentation of the political party system. Local notables usually were unrivalled and some of them enlisted in order to negotiate a rewarding withdrawal.

The big parties also contributed to this, hoping the distribution of votes among independents would benefit their candidates, who were supported by activists and enjoyed abundant financial support. The GPC looked for persons well-rooted in their communities, with party affiliation taking second place. Therefore, tribal leaders, big merchants, and high officials represented its main candidates. The YSP counted mainly on its disciplined cadre regardless of their origins. Tribal notables in the rural areas and Islamic activists in the cities represented the candidates of the Islah. Al-Haqq and the League of the Sons of Yemen were both represented by the Sayyid and prestigious families. The nationalist parties were represented mainly by professionals and activists, though in some cases nominated social notables.

The party system and electoral struggle hardly helped the candidates representing new modernising trends or marginalised segments in Yemeni society. This entails under-representation of workers, peasants, and the more humble strata of the society. Representation of these groups decreased in the 1997 election due to the YSP boycott and in the 2003 election due to the massive hegemony the GPC has. The notables prevailed: great tribal figures, big entrepreneurs, new aristocracy in the south, Islamic activists, and clerics and professionals strongly linked to the ruling GPC. With only two women elected in each of the first two Parliaments and only one in the current (2003) Parliament, the three Parliaments reflect the political and social powers, but not the composition of the society.

Most of the parties drew up programmes and presented them on radio and TV. Recent research on party election manifestos offers a good means of gauging the general tendency of party programmes and to whom parties appeal. The method followed in these studies counts the percentage of sentences a party devotes to each category in its manifesto. This provides a measure of party emphasis on the issue domain represented by that category. This method is designed to measure change in issue content over time across parties and nations. With only three parliamentary elections in Yemen, this method cannot give reliable result. There will have to be several consecutive elections before it is possible to measure change over time. To overcome this obstacle, adding to manifestos the party Charters and political parlance would help bring into focus the general tendencies and changes since 1990.

Election Participation and Voting Behaviour

Several factors contribute to the degree of election participation. According to Michael Rush, electoral turnout varies according to education, occupation, gender, age, religion, ethnicity, residence, and the surrounding environment. There are two categories to look at. The first is the numbers of actual votes cast in relation to numbers of those who are eligible to vote see. The participation goes down to 36.14 per cent, 40.5 per cent and 53 per cent for the 1993, 1997 and 2003 parliamentary elections respectively. Level of education, conservative religious and traditional habits, new democratic procedures, and absenteeism outside the country contribute to this. The other category is the actual votes cast in relation to those who have registered on the electoral rosters see. The participation here was a relatively high 84 per cent in 1993 and 61 per cent in 1997 and 74 in 2003.

The interesting observation is that participation in rural areas, in particular for men, was higher than in urban areas. In the 1993 election the average turnout in the countryside reached 88 per cent, against 81 per cent in the cities. In the 1997 election it was 64 per cent in the countryside and 58 per cent in the cities. In Yemen's traditional society this shows a strong sense of identity amongst the people in rural areas, stronger than amongst their counterparts in urban areas. The rurals usually resist any change that may strike and threaten their identity and existing social arrangements.

Electoral behaviour in Yemen is anchored in the social structure. Unlike the well-established democracies, which have seen the decline of electoral cleavage on politics and the rise of issue voting. It seems that demographic identity predominated in the 1993 election. The distribution of seats was in accordance with the pre-unification geographical division. The GPC won 117 seats in the north and only 3 seats in the south. The YSP won 41 seats in the south and only 15 seats in the north, and the Islah won 62 seats, all in the north. Structural (demographic) cleavage, however, was not purely the electoral preference, as the 1993 election is widely believed to had been distorted by two factors. The first is that both the GPC and the YSP had used mobile military camps to alter the results in some constituencies. The second factor is that there were several indications of a possible agreement between the two parties to direct the election to what they saw as a stable division of power.

In the 1997 election the structural (demographic) cleavage decreased to its minimal level and normative (value) cleavage predominated. The defeat of the YSP in the war deflected electoral preferences. A relaxation in the power struggle after the war allowed the electorate to re-arrange their preferences according to values, traditions, and patrimonial relationships. The Islah party, which did not win a single seat in the south in 1993, won 14 seats in 1997 in the south and 39 in the north. By contrast, in 1997 the GPC won 160 seats in the north and 27 in the south. Value reference evokes group solidarity and thus it is more effective in Yemen to sustain party loyalty than organisational loyalty. This explains why the greatest support for Islah came from rural-tribal areas and the urban-based Islamist faction made only a minor contribution to its performance. Therefore, it can be said tentatively that the high level of electoral volatility and the weak embodiment of political parties in the system go together with a relatively strong correlation between values and party choice in Yemen.

Finally, it is important to note that the dominant parties control the elections in Yemen: in 1993 by both the YSP and the GPC, and in 1997 by the GPC and to some degree the Islah. Domination means a semi-competitive election in which the ruling party uses all advantages including state resources to influence electoral behaviour.

Ahmed Abdelkareem Saif is an Assistant Professor of Politics at AUS and Research Fellow at IAIS, University of Exeter.

——

[archive-e:976-v:14-y:2006-d:2006-08-28-p:report]